IRISH ENVIRONMENTAL LAW ASSOCIATION

NATIONAL MONUMENTS AND INFRASTRUCTURAL PROJECTS

LISA BRODERICK

MATHESON ORMSBY PRENTICE 30 HERBERT STREET DUBLIN 2

NATIONAL MONUMENTS AND INFRASTRUCTURAL PROJECTS

LISA BRODERICK

MATHESON ORMSBY PRENTICE 30 HERBERT STREET DUBLIN 2

NATIONAL MONUMENTS AND INFRASTRUCTURAL PROJECTS

8 December 2005

8 December 2005

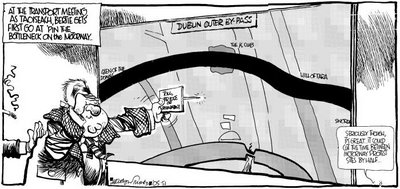

The interaction between the desire to protect our national monuments and the need for prompt completion of infrastructural projects has resulted in an unprecedented level of conflict between interested parties. As anyone who drove to this meeting today, or indeed used public transport to get here, will know our existing road and rail infrastructure is woefully inadequate to deal with the unprecedented demands being placed upon it. As a result huge pressures are being placed on the Government by commuters for them to upgrade our existing road network. The net result is that the NRA (National Roads Authority) have become the largest developer in the country. This is clearly the case given that the total planned investment under the National Development Plan (NDP) is €50 billion over the period 2000-2006. The NRA under the NDP has been assigned the task of providing some 900 km of new motorway and dual carriageway. Ironically, as a result of the planning stages and the data collected from the excavation and post excavation phases of national roads projects much archaeological and historical information has been unearthed which would otherwise have remained covered, inaccessible and perhaps overlooked.

The purpose of this paper is to provide an overview of the legal position in relation to the interaction between the National Roads Authority and the preservation of our national monuments. I will deal with how the system works by setting out the legislative background governing both the National Roads Authority and national monuments. I then intend to analyse recent case law in relation to the issue. Finally I will deal with the most recent litigation involving the construction of the M3.

The purpose of this paper is to provide an overview of the legal position in relation to the interaction between the National Roads Authority and the preservation of our national monuments. I will deal with how the system works by setting out the legislative background governing both the National Roads Authority and national monuments. I then intend to analyse recent case law in relation to the issue. Finally I will deal with the most recent litigation involving the construction of the M3.

Legislative and Administrative Framework Re Archaeological Preservation

The Minister for the Environment, Heritage and Local Government is the national authority with responsibility for protection of archaeological heritage. Legislation governing the protection of archaeological heritage is encapsulated in the National Monuments Acts, 1930 to 2004. Under this legislation, the Minister has an executive and advisory role. His executive role is formed by the exercise of his functions under the aforementioned legislation. However, he also acts as an advisor to certain bodies, such as local authorities. In some cases this role would have a specific statutory basis such as in the Planning and Development Regulations 2001 (SI 600 of 2001) where there are requirements that the Minister be consulted about a proposed development.

Other "bodies" which have a role in relation to the protection of archaeological heritage are the National Monuments Section (NMS) of the Department of the Environment which carries out a wide range of functions under the Acts on behalf of the Minister. These include maintaining the statutory record of monuments and places and they are also responsible for the making of preservation orders and the licensing of archaeological excavations. They also provide advice to planning and other authorities in respect of planning and other development applications, projects and plans Furthermore, the Director of the National Museum of Ireland also has a role in respect of the finding of archaeological objects, in particular the Minister must consult with the Director prior to issuing any directions in accordance with Section 14 of the National Monuments (Amendment) Act 2004. The Legislation also provides that the Minister should consult the Director of the National Museum prior to issuing any excavation licences and the museum itself also deals, on behalf of the Minister, with licensing and the alteration and export of archaeological objects.

Legislative Framework re The NRA

The Roads Act 1993 provides the statutory basis for the National Roads Authority. The Act provides for its interaction with local authorities in the construction of the national road network and gives local authorities a statutory function as roads authorities. Under the Act, road construction undertaken either by the NRA or by local authorities within their own area is "exempted development" for the purposes of the Planning and Development Act 2000. Therefore, road construction itself falls outside the scope of the planning system in respect of requirements to obtain planning permission.

p.2

Notwithstanding this Section 10 of the Planning and Development Act (2000) which deals with the protection of archaeological heritage ensures that local authorities must prepare development plans which set out objectives for the proper planning and development of their areas. The 2000 Act goes on to provide that the inclusion in development plans of objectives for the protection of archaeological heritage is mandatory. Planning legislation prohibits a local authority from engaging in a development that would be a material contravention of its development plan and therefore any objectives of a local authority development plan for the protection of archaeological heritage and indeed for the natural and architectural heritage, should be taken into account in the planning of national roads construction (albeit that the road construction itself falls outside of the planning regime). The Roads Act 1993 provides the statutory basis for compliance by Ireland with the EU Environmental Impact Assessment (85/337/EEC as amended by 97/11/EC).

Section 50 of the 1993 Act requires a local authority to prepare an EIS in respect of any proposed motorway or any other category of road specified in regulations made by the Minister for Environment and Local Government (1.) Section 50 also requires the preparation of an EIS in respect of any road development falling below the threshold set in the Regulations which is still likely to have significant effects on the environment. A road development and one in respect of which an EIS has been prepared cannot proceed unless it is approved by An Bord Pleanala, which must consider the EIS and submission made under a statutory consultation process (Section 51 of the Roads Act 1993 as amended by the Planning and Development Act (2000). As part of their consultation process, a copy of the EIS must be sent by the local authority to the Minister for the Environment, Heritage and Local Government. Section 179 of the Planning and Development Act 2000 provides for a system of consultation and internal decision making for development by local authorities in their own areas. Classes of development to which this section applies includes construction or widening of a road where this would, in an urban area, be 100 metres long or more or would, in any other area be 1 km or more.

Where a proposed development of any specified class would, in the opinion of a local authority affect or be unduly close to any monument protected under the National Monument Acts or any site or feature of archaeological interest (regardless of its status under those Acts) then notice of the proposal must be sent to the Minister for the Environment.

Statutory Definitions of Monuments

It is obviously important to consider the relevant definitions of monuments which are set out in the preamble of the Principal Act (as amended) and are set out below:-

The word "monument" includes the following, whether above or below the surface of the ground or the water and whether affixed or not affixed to the ground:-

(a) any artificial or partly artificial building, structure or erection or group of such buildings, structures or erections,

(b) any cave, stone or other natural product whether or not forming part of the ground, that has been artificially carved, sculptured or worked upon or which (where it does not form part of the place where it is) appears to have been purposely put or arranged in position and

(c) any, or part of any, prehistoric or ancient (i) tomb, grave or burial deposit or (ii) ritual industrial or habitation site, and

(d) any place comprising the remains or traces of any such building, structure or erection, any such cave, stone or natural product or any such tomb, grave, burial deposit or ritual, industrial or habitation site situated on land or in the territorial waters of the State but does not include any building which is for the time being habitually used for ecclesiastical purposes.

A national monument is defined as "A monument or the remains of a monument the preservation of which is a matter of national importance by reason of the historical, architectural, traditional, artistic or archaeological interest attaching thereto and also includes (but not so as to limit, extend or otherwise influence the construction of the foregoing general definition) every monument in Saorstat Eireann to which Ancient Monument Protection Act, 1882 applied immediately before the passing of this Act and

(a) any artificial or partly artificial building, structure or erection or group of such buildings, structures or erections,

(b) any cave, stone or other natural product whether or not forming part of the ground, that has been artificially carved, sculptured or worked upon or which (where it does not form part of the place where it is) appears to have been purposely put or arranged in position and

(c) any, or part of any, prehistoric or ancient (i) tomb, grave or burial deposit or (ii) ritual industrial or habitation site, and

(d) any place comprising the remains or traces of any such building, structure or erection, any such cave, stone or natural product or any such tomb, grave, burial deposit or ritual, industrial or habitation site situated on land or in the territorial waters of the State but does not include any building which is for the time being habitually used for ecclesiastical purposes.

A national monument is defined as "A monument or the remains of a monument the preservation of which is a matter of national importance by reason of the historical, architectural, traditional, artistic or archaeological interest attaching thereto and also includes (but not so as to limit, extend or otherwise influence the construction of the foregoing general definition) every monument in Saorstat Eireann to which Ancient Monument Protection Act, 1882 applied immediately before the passing of this Act and

(1) These Regulations (SI 119 of 1994) specify roads of 4 or more lanes that are 8km or more in a rural area or 500m or more in an urban area.

p.3

the said expression shall be construed as including, in addition to the monument itself, the site of the monument and the means of access thereto and also such portion of the land adjoining such site as may be required to fence, cover in, or otherwise preserve from injury the monument or to preserve the amenities thereof."

It is important to remember that an area is not protected simply by coming within the definition of a monument or national monument. A further step must be taken. A monument is only protected under the National Monuments Acts if it has been made subject to one or other of the monument protection mechanisms established under those Acts. Therefore, it is only protected if it is for example, included in the Record of Monuments and Places, or included in the Register of Historic Monuments, or made subject to a Preservation Order or Temporary Preservation Order or is a national monument in the ownership or guardianship of the Minister or local authority. Due to time constraints, I will not examine how each of these protection mechanisms come into effect but you should be aware of their existence and the particular provisions in relation to same.

In the first decision in relation to Carrickmines and the South Eastern Motorway (Dunne and Lucas -v- Dun Laoghaire and Rathdown County Council (Supreme Court 24 February 2003)) there was a discussion in relation to whether or not the remains of Carrickmines Castle in fact amount to a "national monument". However, this issue was conceded by the local authority in subsequent proceedings which issued in relation to the same development.

Scheme to Facilitate Development Under National Monuments Act 2004

The 2004 Act makes provisions for steps to be taken in circumstances where a national monument is discovered during the course of building works which is unexpected or exceeds expectations in relation to its scope. Under the National Monuments (Amendment) Act, 2004, a procedure is provided for under Section 14 A (4) to be adopted in circumstances where a national monument has been discovered during the carrying out of the road development where neither the approval sought under section 51 of the Roads Act, 1993 nor the EIS which the approval relates deals with the presence of the national monument. It provides that:

1. The road authority carrying out the road development shall report the discovery to the Minister

2. No works which would interfere with the monument shall be carried out (except works urgently required to secure its preservation and such works should be carried out in accordance with such measures as may be specified by the Minister)(3.)

3. The Minister may, at his discretion, issue directions to the road authority concerned for the doing to such monument on one or more of the following matters:

2. No works which would interfere with the monument shall be carried out (except works urgently required to secure its preservation and such works should be carried out in accordance with such measures as may be specified by the Minister)(3.)

3. The Minister may, at his discretion, issue directions to the road authority concerned for the doing to such monument on one or more of the following matters:

(a) preserve it;

(b) renovate or restore it;

(c) excavate, dig, plough or otherwise disturb the ground within, around or in proximity to it;

(d) make record of it;

(e) demolish or remove it wholly or in part or to disfigure, deface, alter or in any manner injure or interfere with it and the road authority shall comply with such directions(4).

(2) Section 14 A (4) (a)

(3) Section 14 A (4) (b)

p.4

4. Prior to making any such directions however, the Minister is obliged to consult in writing with the Director of the National Museum of Ireland. This period for consultation shall not be more than 14 days from the date of the consultative process commenced by the Minister or such other period as may, in any particular case, be agreed between the Minister and the Director of the National Museum of Ireland.(5)

Matters to be taken into account by the Minister

Further guidance is given in the Act in relation to how the Minister may exercise his discretion to issue directions in respect of the treatment of national monuments.

He is not restricted to archaeological considerations but is entitled to consider the public interest notwithstanding that such exercise may involve:

1. injury to or interference with the national monument concerned; or

2. the destruction in whole or in part of the national monument concerned.

The Minister can have regard to the following factors (insofar as he envisages them to be relevant):

1. the preservation, protection or maintenance of the archaeological, architectural, historical or other cultural heritage or amenities of, or associated with the national monument;

2. the nature and extent of any injury or interference with the national monument;

3. any social or economic benefit that would accrue to the State or region in the immediate area in which the national monument is situated as the result of the carrying out of the road development;

4. any matter of policy of the government or the Minister or any other minister of the government;

5. the need to collect or disseminate information on national monuments or in respect of heritage generally; and

6. the cost implications (if any) that would, in the Minister's opinion, occur from the issuing of direction or not issuing a direction under the section.(6)

Even further latitude is given to the Minister as Section 14 A (7) provides that where the Minister considers it expedient to do so in the interest of public health and safety, the Minister may issue such directions without having regard to or having considered matters which, if it was not expedient to do in the interest of public health and safety, the Minister would have had regard to or have considered. For the avoidance of doubt, "approved road development" is defined as the road development approved under either or both Sections 49 and 51 of the Roads Act, 1993. Role of the Road Authority The Act goes on to provide that where the Minister has issued directions to the road authority under Section 14 A (4)(d) of this Act, the road authority shall inform An Bord Pleanala of those directions and of any change to the approved road development which it is satisfied is necessitated by the Minister's direction.(7)

(4) Section 14 A (4) (d)

(5) Section 14 A (4) (e)

(6) Section 14 A (6)

(7) Section 14 B (1)

p.5

Role of An Bord Pleanala

As soon as is practicable after the road authority has informed the Bord of those directions, the Bord shall determine whether as a consequence of those directions, there is a material alteration:

1. to the approved development; or

2. any modification to which the approval under either or both sections 49 and 51 of the Roads Act, 1993 applies.

If the Bord is of the view that the directions made do not give rise to a material alteration, it will advise the road authority concerned of this view. However, if the Bord has formed the view that a material alteration has arisen it shall determine whether or not

(1) to modify the approval concerned or any modification to which that approval is subject or

(2) to add any modification to the approval for the purpose of permitting any changes to the route or design of the approved road development. Furthermore the Bord shall also determine whether or not the material alteration is likely to have significant adverse effects on the environment.(8)

Under the Act the Bord is also obliged to confine itself to considering the directions of the Minister and any proposed change to the approved road developments. Any part of this scheme which has already been approved under section 49 of the Roads Act, 1993 or of the road development which is approved under section 51 of that Act (to which the directions of the Minister do not relate), cannot be put in question as a result of this review. Where the Bord, having regard to all the legal requirements, determines that the material alteration is not likely to have significant adverse effects on the environment, then the Bord shall so advise the road authority so concerned and the Bord shall give its approval subject to any modifications and additions it considers appropriate.(9)

Provision for a Mini-EIS

However, where the Bord makes a determination that the material alteration is likely to have significant adverse effects on the environment, then the Bord shall require an environmental impact statement prepared by the road authority in relation to the change to the approved road development concerned. In the event that the Bord believes that an EIS is necessary, it must contain:

1. the information specified in paragraph 1 of Schedule 6 to the Planning and Development Regulations 2001;

2. the information specified in paragraph 2 to the said Schedule 6 to the extent that

(i) the information is relevant to

(a) the given stage of the consent procedure and to the specific characteristics of the development or type of development concerned and

(b) the environmental features likely to be affected and

(ii) the person or persons preparing the statement may reasonably require to compile it having regard to current knowledge and methods of assessment and

(c) a summary in non technical language of the information required set out above.(10)

8 Section 14 B (3)

9 Section 14 B (4)

10 Section 14 B (6)

p.6

Publication of the EIS When such an EIS has been prepared by the road authority, it must submit a copy of the EIS to the Bord together with a notice in the prescribed form to any prescribed body or person advising that the EIS has been submitted to An Bord Plenala and that before a specified date, submissions must be made in writing to An Bord Plenala in relation to the likely effects on the environment of the proposed change to the approved road development. Furthermore they are obliged to publish a notice in more than one newspaper circulating in the area in which the proposed road development is taking place. They are also obliged to send a copy of the EIS together with a notice in the prescribed form to any other Member State of the European Communities, wherein the road authorities opinion the proposed change to the proposed road development is likely to have significant effect on the environment in that State.(11)

Where an EIS has been submitted, the Bord can confirm the approved road development concerned as affected by the Minister's direction, approve it without modifications, the change to the approved road development or refuse to confirm the approved road development concerned as affected by the Minister's directions.(12) On coming to this view, the Bord is obliged to confine itself to considering the proposed change to the approved road development only. The Bord is not entitled to exercise its function until at least 28 have elapsed until the notice is required to be published and referred to above was first published. The Bord is then obliged to publish in one or more newspaper circulating in the area, its decision. They also must inform any State to which an EIS was sent on the basis that it would be impacted by the "change". Regulations by the Minister The Minister is entitled to make Regulations however each regulation made under this section shall be laid before each house of the Oireachtas as soon as may be after it is made, and if a resolution annulling the regulation is passed by either such house within the next 21 days in which the house has sat after the regulations are laid before it the regulation shall be annulled accordingly but without any prejudice to the validity of anything previously done thereunder(13).

One of the issues which is raised by way of Defence to the second set of proceedings brought in respect of Carrickmines namely Mulcreevy -v- The Minister for the Environment, Heritage and Local Government and Dun Laoghaire Rathdown County Council (14) was that the Applicant delayed in bringing proceedings seeking certiorari and that relief should be denied to him because he failed to initiate his appeal until the period within which the approval order could be annulled by resolution of either House had expired. (Under previous legislation, there was a similar 21 day period within which the House of the Oireachtas could annul any order made.) It was contended on behalf of the Respondents that the Applicants should have instituted the proceedings when the approval order was first made since that was when the ground of challenge "first arose" within the meaning of Order 84, Rule 21 of the Rules of the Superior Court. However, this was dismissed out of hand by the Supreme Court who held that if he had brought this application at that stage the Court would have dismissed it on the ground that it was premature since, for all the Court knew, the Oireachtas might annul the approved order. Therefore, the Applicant was not acting unreasonably in not instituting proceedings to challenge a statutory consent/approval which is devoid of legal effect until the relevant period had expired.

(11) Section 14 B (7)

(12) Section 14 B (8)

(13) Section 14 B (11)

(14) Supreme Court, 27 January 2004

p.7

Public Health and Safety

Finally Section 14 C of the 2004 Act makes provisions for urgent steps that can be taken by the Minister in circumstances where he believes that it is in the interest of public health and safety. As is clear therefore, primary purposes of the 2004 Act was to short circuit the issues in relation to the planning procedure in circumstances where due to preparatory works being undertaking unforeseen national monuments were discovered. As many will be aware, the speedy implementation of this Act gave rise to a considerable amount of criticism especially in circumstances where Section 8 of the Act (not referred to above) made specific provisions in relation to the South Eastern Route (as described in the Third Schedule of the Roads Act, 1993) by Dun Laoghaire Rathdown County Council at a time when the work occurring at this location, close to and indeed involving, the remains at Carrickmines Castle was subject to challenge before the court. Notwithstanding a challenge to this specific section, of the Act (which I will deal with below in greater detail) Section 8 was found to be constitutional.

The Institute of Archaeologists themselves have welcomed the Act in part as they claim that it strengthens the protection of archaeological sites of national importance which are newly discovered on national road schemes like the Viking settlement at Woodstown on the new N25 route, as it provides for an extraordinary "mini" environmental impact statement (EIS) for such sites, even after the rest of the scheme has been approved. On the other hand they have concerns in relation to the fact that the Minister has extraordinary powers to instruct the investigation or demolition of a national monument, stayed only by a period of two weeks for consultation with the Director of the National Museum. The Institute of Archaeologists believes that this is too short a period and that other statutory bodies should be included in the consultation process. They do welcome the fact that it is no longer necessary to seek an archaeological excavation licence for investigations that form part of a major road scheme approved by An Bord Pleanala. This has resulted in the removal of a layer of bureaucracy that was onerous both for the State and the excavating archaeologist; a single road scheme could obviously involve numerous minor investigations all subject to individual licence applications under the previous legislative framework (15).

Case Law

As indicated above, I have made several references to existing case law in relation to this issue. Some of it now is of "historic" interest only (if you pardon the pun) given that enactment of the 2004 Act. It only came into force prior to the last "Carrickmines challenge". However further analysis of how these disputes have been handled before the Court is worthwhile to provide an insight in to how subsequent challenges may proceed and indeed may be avoided. Therefore I have set out below a brief synopsis of the three different challenges which have been brought before the Court arising out of the construction works on the South-Eastern Motorway relating to the discovery of the extent of the remains at Carrickmines Castle.

Dominic Dunne and George Lucas -v- Dun Laoghaire Rathdown County Council (Supreme Court 24 February 2003)

In these proceedings, the Plaintiffs applied for an injunction to prevent the Defendant from removing as part of a road building scheme, parts of a monument on lands which the Defendant owned. They submitted that Section 14 of the 1930 Act, as amended, required that the consent of the Minister for the Environment and Local Government be obtained before the Defendant could interfere with the monuments as, given their contention, it had the status of a national monument. The Defendant's response to this was that by virtue of the Minister having previously granted a licence for excavation of the site in question under Section 26 of the Act of 1930, he had evidenced his consent in writing to the threatened interference complained of by the Plaintiff.

(15) Letter sent to Irish Independent by Eoin Halpin, Chairman of the Institute of Archaeologists of Ireland published on 10 September 2004.

Dominic Dunne and George Lucas -v- Dun Laoghaire Rathdown County Council (Supreme Court 24 February 2003)

In these proceedings, the Plaintiffs applied for an injunction to prevent the Defendant from removing as part of a road building scheme, parts of a monument on lands which the Defendant owned. They submitted that Section 14 of the 1930 Act, as amended, required that the consent of the Minister for the Environment and Local Government be obtained before the Defendant could interfere with the monuments as, given their contention, it had the status of a national monument. The Defendant's response to this was that by virtue of the Minister having previously granted a licence for excavation of the site in question under Section 26 of the Act of 1930, he had evidenced his consent in writing to the threatened interference complained of by the Plaintiff.

(15) Letter sent to Irish Independent by Eoin Halpin, Chairman of the Institute of Archaeologists of Ireland published on 10 September 2004.

p.8

The Supreme Court in a very interesting and well reasoned judgment stated that the requirement in Section 14 of the 1930 Act of the Minister to give consideration to the criteria therein specified was a free-standing one and could not be influenced by any other considerations to which he might have regard in his capacity as Minister for the Environment, more specifically, whether or not he had previously granted a licence pursuant to section 26 of the Act of 1930 for the excavation of another part of the site. There was a further discussion in relation to whether or not damages would be an adequate remedy and indeed, whether or not the undertaking as to damages that would be provided by the Applicant was something that could in fact be relied upon by the Respondent. In this regard, the Supreme Court held that the question of whether damages could be an adequate remedy was largely irrelevant where the claim was to assert a public right as opposed to a private right (indeed damages had not even sought as a relief in the Summons) and the provision for the imposition of criminal penalties for a breach of section 14 of the 1930 Act was also irrelevant when considering whether there were adequate alternative remedies as this would clearly not restore the status quo. Considering the balance of convenience point, the local authority had furnished a considerable amount of information to the Courts in relation to the actual costs which it had incurred in relation to the construction of the motorway and the value of the project on a whole.

However, the Supreme Court criticised this on the basis that the information furnished did not specifically relate to the relief actually being sought by the Applicant and the actual specific costs that would have arisen where the relief sought was granted was not established on the evidence. Therefore, largely on the basis that no separate section 14 consent had been obtained the injunction was furnished. An interesting point raised which still applies is whether or not, it is appropriate for a Minister who has already granted an excavation licence wearing his hat of "road builder" should then be the person who is approached to form a view in relation to the preservation of national monuments in circumstances where this would almost inevitably bring him into conflict with the terms of the licence already given from the point of view of the road construction. This matter did not progress to full plenary hearing as following same the local authority applied for a "separate" section 14 licence relating to the works which are complained of in the initial proceedings.

Michael Mulcreevy -v- The Minister for the Environment, Heritage and Local Government and Dun Laoghaire Rathdown County Council (Supreme Court 27 January 2004)

Once the section 14 Consent had been applied for the joint consent of the local authority and the Environment Minister was given on the 3 July 2003 and on the same day the Environment Minister made the National Monuments (Approval of Joint Consent) Order 2003. As provided for in the legislation the Order was laid before both House of the Oireachtas and would not become effective until 21 sitting days of both house had elapsed and no resolution to annul the order had been passed by either house. Therefore the Order did not come into effect until 2 December 2003. An Interlocutory Injunction granted in the Dunne and Lucas proceedings was discharged by the High Court on 8 December 2003 and on that day the local authority stated that it would be taking the appropriate steps to implement the approval given by the Environment Minister.

On 23 December 2003, an application was made on behalf of the Plaintiffs to the High Court for leave to issue proceedings by way of judicial review claiming an order of certiorari and an order of prohibition prohibiting the local authority from in any way demolishing, removing, disfiguring, defacing, etc. the monument and an injunction against the local authority to the same effect pending the hearing of these proceedings. I have already dealt with earlier on in the paper, the unsuccessful arguments that were made in relation to the delay on behalf of the Applicant in bringing these proceedings. There was a further discussion in relation to whether or not the Applicant had any locus standi within which to bring the proceedings but both the High Court and the Supreme Court determined that he did in fact have such locus standi.

An interesting issue was raised in relation to the standard applicable to an application for leave in circumstances where the other party was on notice of the application. The Supreme Court agreed that where the application has been made on notice and the other side has been heard, it may well be that there will be no outstanding issue of fact which has to be resolved at a full hearing and

Once the section 14 Consent had been applied for the joint consent of the local authority and the Environment Minister was given on the 3 July 2003 and on the same day the Environment Minister made the National Monuments (Approval of Joint Consent) Order 2003. As provided for in the legislation the Order was laid before both House of the Oireachtas and would not become effective until 21 sitting days of both house had elapsed and no resolution to annul the order had been passed by either house. Therefore the Order did not come into effect until 2 December 2003. An Interlocutory Injunction granted in the Dunne and Lucas proceedings was discharged by the High Court on 8 December 2003 and on that day the local authority stated that it would be taking the appropriate steps to implement the approval given by the Environment Minister.

On 23 December 2003, an application was made on behalf of the Plaintiffs to the High Court for leave to issue proceedings by way of judicial review claiming an order of certiorari and an order of prohibition prohibiting the local authority from in any way demolishing, removing, disfiguring, defacing, etc. the monument and an injunction against the local authority to the same effect pending the hearing of these proceedings. I have already dealt with earlier on in the paper, the unsuccessful arguments that were made in relation to the delay on behalf of the Applicant in bringing these proceedings. There was a further discussion in relation to whether or not the Applicant had any locus standi within which to bring the proceedings but both the High Court and the Supreme Court determined that he did in fact have such locus standi.

An interesting issue was raised in relation to the standard applicable to an application for leave in circumstances where the other party was on notice of the application. The Supreme Court agreed that where the application has been made on notice and the other side has been heard, it may well be that there will be no outstanding issue of fact which has to be resolved at a full hearing and

p.9

that the Court hearing the application for leave may indeed be in as good a position as the Court which shares the ultimate application to determine the legal issue involved but did not make a formal determination in relation to this point in the context of these proceedings. In the course of his application the Applicant had argued the following. Firstly, the reasons given by the Environment Minister on 3 July approving the joint consent by him and the local authority were inadequate. The Minister had deemed that it was required for "public interest in construction of the motorway".

The Applicant argued that this specific reason was not provided for in the legislation and that therefore the Minister was not entitled to rely upon it. This was not accepted by the Supreme Court, they felt that the Minister specifically had a quite residual discretion to permit an interference with national monuments, subject to the qualification that the appropriate order had to be laid before the House of the Oireachtas. The Order was, however, further challenged on the ground that the 1996 Order made by the Government in purported exercise of the power conferred to them by Section 9(2) of the Ministers and Secretaries Act 1924 provided that the consent of the Commissioners of Public Works in Ireland ('the Commissioners'), which together with the consent of the local authority, was formally a precondition to a lawful interference with the national monument was now no longer required. In its place there is a requirement that the consent of the Arts Minister, on whom there was already vested the ultimate power of approval be obtained. The net effect of this obviously meant that instead of a three stage system, the matter was reduced to two stages with only two bodies, the Minister and the local authority having to sign off in relation to same. The Applicant had argued that such a change to the procedure could not be achieved by way of delegated legislation. A further Order was made on foot of the Ministers and Secretaries (Amendment) Act 193916 whereby the relevant function of the Arts Minister were transferred to the Minister for the Environment.

The Respondents argued that the effect of the 1996 Order was simply to transfer the functions of the Commissioners under the 1930 Act and the 1994 Act to the Arts Minister. However, the Supreme Court did not accept this. They said that it was impossible to avoid the conclusion that it did more; that it purported to effect an amendment of the Statutory Scheme established under Section 15 of the 1994 Act. Therefore, it was difficult to avoid the conclusion that construction in accordance with Article 15(2)(1) of the Constitution(17).

They held that Section 9(2) of the Minister's and Secretaries Act 1924 cannot be interpreted as conferring any power in the Government to make an Order having that effect. On this basis the Supreme Court decided that there was an arguable ground and therefore granted the injunction. Interestingly in this case, the Supreme Court was asked to consider the validity of the 1996 Order and the 2002 Order (transferring functions between Ministers) on the ground that in permitting the Environment Minister to make a decision granting an approval in respect of consent to which he was already a party it had violated the requirement as to fair procedures guaranteed by Article 40.3 of the Constitution. It was said that this was a breach of the requirement of natural justice, nemo iudex in causa sua (i.e. that no one should be judge in his own cause). The Supreme Court held, however, that in accordance with the decision of O'Brien -v- Bord Na Mona(18) the nemo iudex principle had no necessary application to administrate procedures of that nature. Therefore the Applicant did not show an arguable or statable case based on that ground.

(16) Section 6 (1)

(17) (which provides that the sole and exclusive power of making laws for the State is hereby vested in the Oireachtas; no legislative authority has power to make laws for the State) 18 [1983] IR 255

The Applicant argued that this specific reason was not provided for in the legislation and that therefore the Minister was not entitled to rely upon it. This was not accepted by the Supreme Court, they felt that the Minister specifically had a quite residual discretion to permit an interference with national monuments, subject to the qualification that the appropriate order had to be laid before the House of the Oireachtas. The Order was, however, further challenged on the ground that the 1996 Order made by the Government in purported exercise of the power conferred to them by Section 9(2) of the Ministers and Secretaries Act 1924 provided that the consent of the Commissioners of Public Works in Ireland ('the Commissioners'), which together with the consent of the local authority, was formally a precondition to a lawful interference with the national monument was now no longer required. In its place there is a requirement that the consent of the Arts Minister, on whom there was already vested the ultimate power of approval be obtained. The net effect of this obviously meant that instead of a three stage system, the matter was reduced to two stages with only two bodies, the Minister and the local authority having to sign off in relation to same. The Applicant had argued that such a change to the procedure could not be achieved by way of delegated legislation. A further Order was made on foot of the Ministers and Secretaries (Amendment) Act 193916 whereby the relevant function of the Arts Minister were transferred to the Minister for the Environment.

The Respondents argued that the effect of the 1996 Order was simply to transfer the functions of the Commissioners under the 1930 Act and the 1994 Act to the Arts Minister. However, the Supreme Court did not accept this. They said that it was impossible to avoid the conclusion that it did more; that it purported to effect an amendment of the Statutory Scheme established under Section 15 of the 1994 Act. Therefore, it was difficult to avoid the conclusion that construction in accordance with Article 15(2)(1) of the Constitution(17).

They held that Section 9(2) of the Minister's and Secretaries Act 1924 cannot be interpreted as conferring any power in the Government to make an Order having that effect. On this basis the Supreme Court decided that there was an arguable ground and therefore granted the injunction. Interestingly in this case, the Supreme Court was asked to consider the validity of the 1996 Order and the 2002 Order (transferring functions between Ministers) on the ground that in permitting the Environment Minister to make a decision granting an approval in respect of consent to which he was already a party it had violated the requirement as to fair procedures guaranteed by Article 40.3 of the Constitution. It was said that this was a breach of the requirement of natural justice, nemo iudex in causa sua (i.e. that no one should be judge in his own cause). The Supreme Court held, however, that in accordance with the decision of O'Brien -v- Bord Na Mona(18) the nemo iudex principle had no necessary application to administrate procedures of that nature. Therefore the Applicant did not show an arguable or statable case based on that ground.

(16) Section 6 (1)

(17) (which provides that the sole and exclusive power of making laws for the State is hereby vested in the Oireachtas; no legislative authority has power to make laws for the State) 18 [1983] IR 255

p.10

Dominic Dunne -v- The Minister for the Environment, Heritage and Local Government, Ireland, The Attorney General and Dun Laoghaire Rathdown County Council (High Court 7 September 2004)

The National Monuments (Amendment) Act 2004 came into force on 18 July 2004. As is referred to above Section 8 of the Act introduced special provision in relation to the South-Eastern Route, which basically amounted to a truncated procedure to be adopted to complete the Carrickmines stretch of the motorway and did not provide either for a mini EIS or Bord Approval but rather just Ministerial Directions In accordance with the Act, on 21 July 2004, DLR CC applied to the Minister for directions under Section 8.

The application set out the works which DLR CC, subject to terms and conditions or any direction which the Minster might issue, proposed to be carried out to the site of Carrickmines Castle. It was stated that the works in question are in respect of "outstanding archaeological resolution measured at the site". Subsequently by letter dated 12 August 2004, the chief archaeologist in the National Monuments Section of the Minister's Department agreed method statements submitted by the Council. On 5 August 2004, the Council was informed that the Minister had issued directions "in respect of the amending works as the affect any national monument" and the directions were set out in the appendix attached to the letter.

In the appendix the directions were described as being for archaeological resolution of the Carrickmines Castle site. The position of the State and Council in these proceedings is that the directions relate solely to the archaeological excavation of the site. They do not contain or involve any alteration material or otherwise to the road development approved under the 1993 Act. Works recommenced at Carrickmines Castle on 16 August 2004. The position of the Defendants was that the works in question were archaeological works and they were being carried out in accordance with the method statements submitted by the Council and their archaeological consultants and approved by the National Monuments Section of the Minister's Department. Proceedings were commenced on 18 August, 2004 (two days after works commenced).

The Plaintiff sought the following relief:-

1. a declaration of Section 8 of the 2004 Act is unconstitutional;

2. a declaration of Section 8 of the 2004 Act is contrary to the provisions of European law particularly in relation to the directives concerning the requirements for an EIS in the alternative a declaration that the directions by the Minister pursuant to Section 8 are a nullity by reason of the failure of the Minister to comply and/or to have regard to the requirements of the directive in relation to environmental impact assessments.

3. finally, they sought an injunction restraining the Council from demolishing, removing, in whole or in part, disfiguring or defacing the remains of Carrickmines Castle.

Ultimately, Ms Justice Laffoy held that the works regulated in accordance with section 8 do not fall within the ambit of Point 13 of Annex 2 of the EIS Directive and that the directions which have been issued by the Minister under section 8 do not constitute a development consent and accordingly that the implementation of the directions will not contravene the Directive. In relation to the constitutional challenge, the issue was raised again in relation to the question of locus standi for constitutional challenges. In this regard, case law has shown that the Courts will only entertain a constitutional challenge where it has demonstrated that litigants rights have been either infringed or threatened. Secondly, the Courts will only listen to arguments based on the Plaintiff's own personal situation and will generally not allow arguments based on a jus tertii. However, since every member of the public has an interest in seeing the fundamental law of the State is not defeated the Courts will permit a citizen to challenge an actual or threatened breach of a constitutional norm where there is no other suitable Plaintiff or where the threatened breach is likely to affect all citizens in general.

Justice Laffoy found that it was not inconceivable that in a hypothetical case a person in the position of the Plaintiff or concerned private citizen could successfully challenge a statutory measure on the basis that it purported to permit a clear-cut breach of the State's duty to protect national heritage but she found that this was not the case here and in inviting the Court to review section 8 in light of the State's

The National Monuments (Amendment) Act 2004 came into force on 18 July 2004. As is referred to above Section 8 of the Act introduced special provision in relation to the South-Eastern Route, which basically amounted to a truncated procedure to be adopted to complete the Carrickmines stretch of the motorway and did not provide either for a mini EIS or Bord Approval but rather just Ministerial Directions In accordance with the Act, on 21 July 2004, DLR CC applied to the Minister for directions under Section 8.

The application set out the works which DLR CC, subject to terms and conditions or any direction which the Minster might issue, proposed to be carried out to the site of Carrickmines Castle. It was stated that the works in question are in respect of "outstanding archaeological resolution measured at the site". Subsequently by letter dated 12 August 2004, the chief archaeologist in the National Monuments Section of the Minister's Department agreed method statements submitted by the Council. On 5 August 2004, the Council was informed that the Minister had issued directions "in respect of the amending works as the affect any national monument" and the directions were set out in the appendix attached to the letter.

In the appendix the directions were described as being for archaeological resolution of the Carrickmines Castle site. The position of the State and Council in these proceedings is that the directions relate solely to the archaeological excavation of the site. They do not contain or involve any alteration material or otherwise to the road development approved under the 1993 Act. Works recommenced at Carrickmines Castle on 16 August 2004. The position of the Defendants was that the works in question were archaeological works and they were being carried out in accordance with the method statements submitted by the Council and their archaeological consultants and approved by the National Monuments Section of the Minister's Department. Proceedings were commenced on 18 August, 2004 (two days after works commenced).

The Plaintiff sought the following relief:-

1. a declaration of Section 8 of the 2004 Act is unconstitutional;

2. a declaration of Section 8 of the 2004 Act is contrary to the provisions of European law particularly in relation to the directives concerning the requirements for an EIS in the alternative a declaration that the directions by the Minister pursuant to Section 8 are a nullity by reason of the failure of the Minister to comply and/or to have regard to the requirements of the directive in relation to environmental impact assessments.

3. finally, they sought an injunction restraining the Council from demolishing, removing, in whole or in part, disfiguring or defacing the remains of Carrickmines Castle.

Ultimately, Ms Justice Laffoy held that the works regulated in accordance with section 8 do not fall within the ambit of Point 13 of Annex 2 of the EIS Directive and that the directions which have been issued by the Minister under section 8 do not constitute a development consent and accordingly that the implementation of the directions will not contravene the Directive. In relation to the constitutional challenge, the issue was raised again in relation to the question of locus standi for constitutional challenges. In this regard, case law has shown that the Courts will only entertain a constitutional challenge where it has demonstrated that litigants rights have been either infringed or threatened. Secondly, the Courts will only listen to arguments based on the Plaintiff's own personal situation and will generally not allow arguments based on a jus tertii. However, since every member of the public has an interest in seeing the fundamental law of the State is not defeated the Courts will permit a citizen to challenge an actual or threatened breach of a constitutional norm where there is no other suitable Plaintiff or where the threatened breach is likely to affect all citizens in general.

Justice Laffoy found that it was not inconceivable that in a hypothetical case a person in the position of the Plaintiff or concerned private citizen could successfully challenge a statutory measure on the basis that it purported to permit a clear-cut breach of the State's duty to protect national heritage but she found that this was not the case here and in inviting the Court to review section 8 in light of the State's

p.11

duty to safeguard the national heritage and the other requirements of the common good, the Plaintiff was asking the Court, to use the metaphor used by Keane CJ in TD -v- Minister for Education(19) to cross "a Rubicon and undertake a role which is conferred by statute on the Oireachtas under the Constitution, the Courts cannot do this." Therefore the Plaintiff's claim that section 8 was invalid by reference to Articles 5, 10 and 40 of the Constitution failed. This decision was appealed to the Supreme Court and heard by them on 7 April 2005. The Supreme Court is due to hand down its decision on 13 December 2005. Clearly no interlocutory relief was sought to restrain the works of the local authority and the NRA pending the Appeal as they have now completed that stretch of the M50 that is adjacent to Carrickmines. A further appeal in relation to the costs of the matter has not yet been set down for hearing.

The M3!

The NRA has attempted to pre-empt matters by producing publications such as 'The NRA, The M3 and Archaeology - The Facts'(20). An article published in the Summer 2004 edition of Archaeology Ireland and written by Gabriel Cooney entitled 'Tara and the M3- Putting the Debate in Context' advocates restraint. He advises that notwithstanding the imperfect, flawed nature of the planning process, parties have to operate within it.

In the case of the M3 the planning process has been pursued over several years, An Bord Pleanala has adjudicated on it and the motorway is going to be built. It is in this context that he advocates an informed and non hysterical consideration of all of the issues and facts. He points out the ultimate irony with all of these matters which is that some of the objections to the route arise from the fact that so many potential archaeological sites have been recognised along the proposed route. However it is only as a result of the site survey carried out as part of the assessment of the route that these sites were recognised. There had been no surviving trace of them above the ground as continuous agricultural usage of the landscape over time has gradually degraded then to a stage where they only survive underground.

In relation to the future generally he hopes that the coming into force of the Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) Directive will lead to a better integration of archaeological, environmental and landscape concerns with other socio-economic requirements. This Directive was transposed into Irish law and came into effect on July 20 200421. It requires that an environmental assessment must be carried out on land use plans which are likely to have significant effects on the environment. Therefore from 21 July 2004 any regional planning guidelines, city and council development plans, planning schemes in respect of Strategic Development Zones and in specific circumstances development plans and planning schemes must comply with requirements set out in the Directive. However the implementation of the Directive obviously post dates the commencement of the planning process for the M3.

As can be seen by the chronology furnished in relation to the cases concerning Carrickmines in the past Applicants have used very ingenious means of challenging actions and licences issued in accordance with the appropriate legislation. The PRO of "Save Tara Skryne Valley Group" Vincent Salafia went on record to state that "The 2004 Amendment butchers all preceding ones [Acts] removing procedural and substantive safeguards and rendering the Act toothless ………. [It] is not designed to protect monuments but to facilitate road

The M3!

The NRA has attempted to pre-empt matters by producing publications such as 'The NRA, The M3 and Archaeology - The Facts'(20). An article published in the Summer 2004 edition of Archaeology Ireland and written by Gabriel Cooney entitled 'Tara and the M3- Putting the Debate in Context' advocates restraint. He advises that notwithstanding the imperfect, flawed nature of the planning process, parties have to operate within it.

In the case of the M3 the planning process has been pursued over several years, An Bord Pleanala has adjudicated on it and the motorway is going to be built. It is in this context that he advocates an informed and non hysterical consideration of all of the issues and facts. He points out the ultimate irony with all of these matters which is that some of the objections to the route arise from the fact that so many potential archaeological sites have been recognised along the proposed route. However it is only as a result of the site survey carried out as part of the assessment of the route that these sites were recognised. There had been no surviving trace of them above the ground as continuous agricultural usage of the landscape over time has gradually degraded then to a stage where they only survive underground.

In relation to the future generally he hopes that the coming into force of the Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) Directive will lead to a better integration of archaeological, environmental and landscape concerns with other socio-economic requirements. This Directive was transposed into Irish law and came into effect on July 20 200421. It requires that an environmental assessment must be carried out on land use plans which are likely to have significant effects on the environment. Therefore from 21 July 2004 any regional planning guidelines, city and council development plans, planning schemes in respect of Strategic Development Zones and in specific circumstances development plans and planning schemes must comply with requirements set out in the Directive. However the implementation of the Directive obviously post dates the commencement of the planning process for the M3.

As can be seen by the chronology furnished in relation to the cases concerning Carrickmines in the past Applicants have used very ingenious means of challenging actions and licences issued in accordance with the appropriate legislation. The PRO of "Save Tara Skryne Valley Group" Vincent Salafia went on record to state that "The 2004 Amendment butchers all preceding ones [Acts] removing procedural and substantive safeguards and rendering the Act toothless ………. [It] is not designed to protect monuments but to facilitate road

(19) [2001] 4 IR 259 at 288

(20) Available from the NRA website.

(21) Transposed into Irish law by EC (Environmental Assessment of certain Plans and Programmes) Regulations 2004 and the Planning and Development (SEA) Regulations 2004.

(20) Available from the NRA website.

(21) Transposed into Irish law by EC (Environmental Assessment of certain Plans and Programmes) Regulations 2004 and the Planning and Development (SEA) Regulations 2004.

p.12

Mr Salafia secured leave from the High Court in 4 July 2005 to seek to re-route the M3 motorway. The proceedings were issued against the Minister, Meath County Council, Ireland and the Attorney General. Leave was granted by Justice McKechnie for Mr Salafia to bring proceedings challenging the directions made by Environment Minister Dick Roche over treatment of 38 known archaeological sites along a stretch of the proposed motorway. Although no written judgment has been made available in relation to the leave application it would appear from newspaper reports that Mr Salafia has argued that the Directions issued were in excess of the Minister's powers and were issued under the incorrect provisions of the 2004 Act. Furthermore, he has argued that the relevant provisions are unconstitutional in that they fail to afford adequate protection for national monuments. He has also claimed that the Minister has failed to have regard to the State's obligation in regard to national monuments. He however sought an Order quashing the Minister's directions and a declaration that the Hill of Tara/Skryne Valley area constitutes a national monument or a series of monuments, together with other reliefs.

Justice McKechnie stated that he was satisfied that Mr Salafia had established an arguable case but indicated that he was not embarking on any substantial assessment or evaluation of the facts. The substantial hearing has now been listed for hearing in before Justice Finnegan on 12 December 2005 and Mr Salafia did not seek any interim relief pending the substantial hearing.

It is clear therefore that the law in this area will remain in a state of flux. The outcome of the awaited Supreme Court Appeal in the Dunne case together with the substantive hearing of the Salafia case should serve to fully "test" the provisions of the 2004 Act. However, given the ingenuity that has been shown to date by environmentalists who have challenged infrastructural projects, even the most comprehensive decisions are unlikely to resolve the ongoing friction between those determined to protect the ancient and those who wish to embrace the future!

Justice McKechnie stated that he was satisfied that Mr Salafia had established an arguable case but indicated that he was not embarking on any substantial assessment or evaluation of the facts. The substantial hearing has now been listed for hearing in before Justice Finnegan on 12 December 2005 and Mr Salafia did not seek any interim relief pending the substantial hearing.

It is clear therefore that the law in this area will remain in a state of flux. The outcome of the awaited Supreme Court Appeal in the Dunne case together with the substantive hearing of the Salafia case should serve to fully "test" the provisions of the 2004 Act. However, given the ingenuity that has been shown to date by environmentalists who have challenged infrastructural projects, even the most comprehensive decisions are unlikely to resolve the ongoing friction between those determined to protect the ancient and those who wish to embrace the future!

(22) Article by Vincent Salafia published in The Irish Times on 17 August 2004.

This material has been prepared for the purposes of a general briefing only. It should not be relied upon as a substitute for legal advice.

©Lisa Broderick Litigation and Dispute Resolution Department Matheson Ormsby Prentice Solicitors 30 Herbert Street Dublin 2 8 December 2005.

p.13

1 comment:

While a good chronological account of recent events, I think this paper is overly prodeveloper and paints heritage campaigners as anti-future. We just have a better image of the future, which actually is a product of sustainable development.

Post a Comment